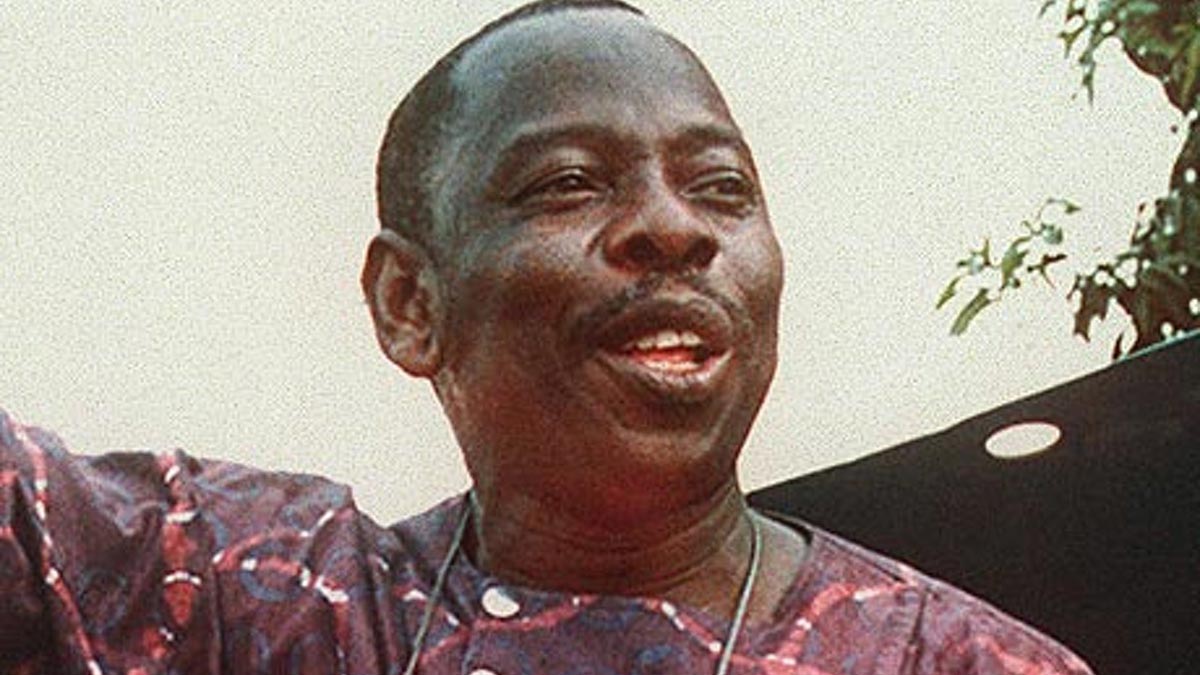

On November 10, 1995, the struggle for environmental justice and ethnic equity in Nigeria met its most tragic chapter when Ken Saro-Wiwa, a renowned playwright, activist, and environmental crusader, was executed alongside eight others. Their deaths, carried out by hanging in Port Harcourt prison, marked a dark turning point in Nigeria’s political history, a moment that not only shocked the nation but drew global outrage.

Saro-Wiwa’s final words before his execution “Lord, take my soul, but the struggle continues,” echoed with defiance and sorrow. His body, limp from a hastily constructed gallows that failed multiple times, symbolized the brutal suppression of dissent under Nigeria’s military regime. It had been thirty years since a death sentence had been carried out in that prison, last used during British colonial rule. But on that day, under the authority of General Sani Abacha’s dictatorship, Nigeria revived the gallows for its own.

The Ogoni Nine, as they came to be known, were executed after a controversial military tribunal accused them of involvement in the murder of four Ogoni elders. The trial was widely condemned by human rights organizations and the international community as flawed and politically motivated. The men were moved before dawn from their military detention camp to the prison and hanged by 3:15pm. The entire process was sealed off from their families no final farewells, no public dignity.

Saro-Wiwa’s crime, in the eyes of the regime, was his relentless activism on behalf of the Ogoni people, a minority ethnic group in Nigeria’s oil-rich Niger Delta. Decades of oil exploration by multinational giants like Shell had left Ogoniland devastated, with polluted rivers, destroyed farmland, and air choked with gas flares. Despite generating over 80% of Nigeria’s foreign revenues, the Delta remained impoverished and ignored. Roads, water, electricity basic infrastructure was absent.

From his early years, Saro-Wiwa questioned the oil exploitation in the region. Even at 17, he wrote letters to the government and oil companies asking how local communities would benefit from their land’s riches. But he would later transform his discontent into organized resistance. In 1990, he co-founded the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), which launched the now-famous Ogoni Bill of Rights, demanding political autonomy, control over local resources, and protection from environmental degradation.

His activism gained momentum. In January 1993, nearly 300,000 Ogonis out of a population of half a million marched under his leadership to protest against Shell and the Nigerian government. The peaceful protest, one of the largest in Nigeria’s history, drew international attention. Environmental organizations such as Greenpeace backed the movement, and Saro-Wiwa took the Ogoni cause to global forums including the United Nations.

But as international awareness grew, so did the crackdown. Riots broke out later that year. Oil pipelines were sabotaged. Shell suspended its operations in Ogoniland. The Nigerian government, eager to protect its oil interests, responded with a brutal military task force. Reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch described widespread abuses: extrajudicial killings, rape, torture, and forced evictions.

Amid escalating tensions, internal divisions within MOSOP also surfaced. Saro-Wiwa, now seen as the face of the resistance, clashed with more pacifist members like Edward Kobani, a former friend and fellow Ogoni leader. The rift deepened as some accused the moderates of collaborating with Shell and the government — though no evidence ever substantiated those claims.

Tragedy struck on May 21, 1994, when four Ogoni elders, including Kobani and two of Saro-Wiwa’s in-laws, were brutally murdered by a mob. Although Saro-Wiwa was not present, he and eight other MOSOP leaders were arrested, charged with inciting the violence, and sentenced to death after a trial marred by allegations of bribed witnesses and judicial bias.

Their executions provoked international condemnation. Nigeria faced economic sanctions and was suspended from the Commonwealth. Shell came under intense scrutiny, accused of complicity in the events an accusation it has denied but which continues to shadow its legacy in the region.

Thirty years later, on June 12, 2025 Nigeria’s Democracy Day, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu posthumously pardoned the Ogoni Nine, hailing them as national heroes and bestowing prestigious national honors. For families like that of Noo Saro-Wiwa, Ken’s daughter, the gesture was emotional but incomplete. “Pardons are not enough,” many in Ogoniland say. The region remains underdeveloped, with ongoing oil pollution, environmental neglect, and unfulfilled promises of justice.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), in a 2011 report, found that it could take up to 30 years to clean up the environmental damage in Ogoniland. Yet more than a decade later, little progress has been made. Communities still live with contaminated water, health hazards, and economic hardship. The promises of environmental restoration and compensation remain largely unfulfilled.

Ken Saro-Wiwa’s legacy lives on in Nigeria’s environmental justice movement and in global activism. His life as a writer, satirist, and fierce advocate for his people reflects the enduring struggle of minority voices against oppressive powers. His radio dramas and essays mocked the political elite and the corruption that followed Nigeria’s independence. In one of his short stories, Africa Kills Her Sun, he eerily foreshadowed his own death: a man condemned to execution writes a farewell letter to his lover, urging her not to mourn.

Today, his story serves as a painful reminder of Nigeria’s past sins and its continuing failure to reconcile with the people of the Niger Delta. The fight Saro-Wiwa led for dignity, environmental justice, and the rights of minority groups remains unresolved.

The gallows may have silenced his voice that day in 1995, but his words, his vision, and the injustice he fought against still echo loudly across the swamps and towns of the Niger Delta and in the conscience of a nation yet to atone.

Leave a comment