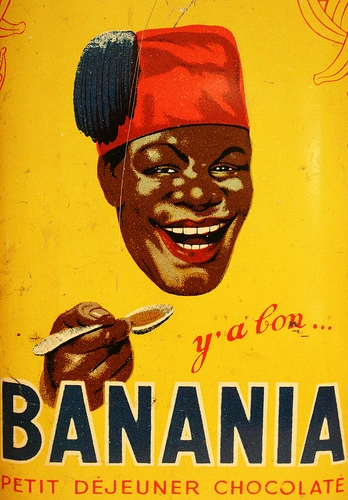

The story of Banania, France’s iconic chocolate-flavoured banana powder drink, is deeply intertwined with the country’s colonial past. First introduced during World War I, the brand became famous not only for its sweet taste but also for its controversial mascot: a caricature of a Black Senegalese Tirailleur soldier wearing a red fez, smiling with exaggerated features, and accompanied by the infamous slogan “Y’a bon” (“It’s good” in broken French).

Launched in 1915, Banania arrived at a time when 200,000 African soldiers from French colonies were fighting in Europe, Africa, and Anatolia many of them forcibly recruited. The mascot was modeled after the tirailleurs sénégalais, colonial riflemen first recruited in 1857, known for their bravery but also remembered as victims of exploitation. By depicting a cheerful African soldier enjoying Banania, founder Pierre Lardet cleverly mixed patriotism, colonial propaganda, and consumerism, encouraging French citizens to view the drink as both nourishing and symbolic of empire.

Throughout the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, Banania became a household name in France. Its mascot appeared everywhere—on posters, packaging, comics, promotional items, toys, and even trucks during the Tour de France. The drink became a symbol of colonial pride, reinforcing racial stereotypes while celebrating France’s use of African soldiers in both World Wars. During its golden years, Banania tripled production, dominating the market before facing competition from Nesquik in the 1960s.

However, as African nations gained independence in the 1950s and 1960s, Banania’s mascot became increasingly controversial. To anti-colonial activists, the tirailleur caricature embodied racism and colonial oppression. Senegal’s first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, famously wrote in 1948: “I will tear up the Banania smiles from all the walls of France.” Similarly, Martinican philosopher Frantz Fanon criticized the brand in his 1952 classic Black Skin, White Masks, highlighting how it reinforced harmful stereotypes about Black people in French society.

Despite criticism, Banania kept updating its mascot. In 1967, the company simplified the soldier’s face into a geometric design, retiring the “Y’a bon” slogan in 1977. Later, in the 1980s and 1990s, a cartoon child appeared on some packaging. By 2004, when the brand was acquired by Nutrimaine, a new “grandson” of the original tirailleur was unveiled, meant to symbolize diversity and integration. Yet his wide smile, red fez, and exaggerated features sparked backlash, with activists calling it a modernized version of the same colonial stereotype.

Writers and activists, especially within Europe’s Black communities, denounced Banania’s persistence as a symbol of France’s failure to reckon with its colonial past. Online petitions demanded the mascot’s removal, while graphic designers like Awatif Bentahar proposed alternative, decolonized packaging that celebrated Banania’s history without racist imagery.

Today, Banania boxes featuring the “grandson” mascot can still be found in French supermarkets. For many, the brand remains nostalgic, tied to childhood memories of breakfast. But for others, it is a painful reminder of France’s colonial propaganda and racial caricatures. As Etienne Achille, professor of French and Francophone studies at Villanova University, explains: “Only the complete imbrication of the colonial into popular culture can explain why Banania can continue to operate with impunity. In other countries, this would not be possible.”

The Banania controversy continues to spark debate about racism, colonial memory, and cultural identity in modern France. While the drink itself may be sweet, its legacy is undeniably bitter a reminder that everyday consumer products often carry extraordinary and painful histories.

Leave a comment