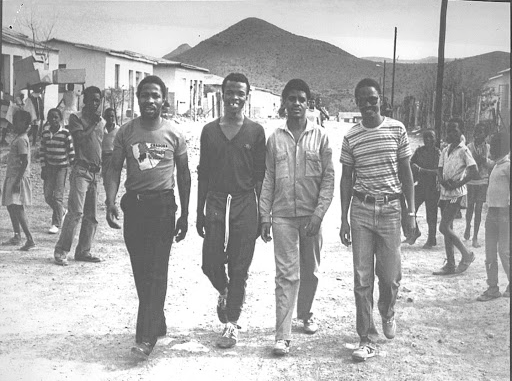

Nearly four decades after one of the most harrowing political crimes of South Africa’s apartheid era, the country has reopened an inquest into the brutal murders of the “Cradock Four”: Fort Calata, Matthew Goniwe, Sicelo Mhlauli, and Sparrow Mkonto in a renewed effort to bring long-overdue justice to their families and expose the systemic atrocities committed under white minority rule. On the night of June 27, 1985, these four Black anti-apartheid activists were returning from a community meeting near Port Elizabeth (now Gqeberha) when they were stopped at a roadblock set up by apartheid security forces. They were abducted, tortured, and later found murdered, their bodies discarded in remote locations, burned and mutilated.

The apartheid regime initially denied any involvement, but leaked documents and testimonies revealed the men had been targeted by the state for their political organizing. Evidence emerged of a government death warrant authorizing their execution, confirming the killings were premeditated. Despite two inquests under the apartheid regime in 1987 and 1993, no individuals were held responsible. The first inquest was conducted entirely in Afrikaans, denying the victims’ families any meaningful participation. “It was clear that four people were murdered,” said Lukhanyo Calata, son of Fort Calata, “but the courts said no one could be blamed.”

Following South Africa’s democratic transition in 1994, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) confirmed that the Cradock Four were killed for their activism. Several former apartheid police officers confessed to being involved but refused to provide full disclosure and were subsequently denied amnesty. To this day, no one has been prosecuted.

Now, a new inquest has begun in Gqeberha, reigniting hopes for justice. Families of the slain activists are calling for the truth about who ordered the killings and who carried them out. “For 40 years, we’ve waited for justice,” Lukhanyo Calata told local media. “We hope this process will finally expose the truth.”

The reopening of the Cradock Four case has renewed focus on South Africa’s broader failure to prosecute apartheid-era crimes, despite the TRC’s recommendations. Families of other victims such as Nokuthula Simelane, a 23-year-old Umkhonto we Sizwe (ANC military wing) operative who disappeared in 1983, have also been left without answers. Simelane was reportedly tortured and killed by apartheid police, yet her body has never been found, and no one has been held accountable. At the TRC, several officers applied for amnesty, with conflicting testimonies about her fate. One claimed she was murdered and buried in the North West province, another that she was turned informant and sent back to Swaziland. Her family continues to live with the agony of not having a grave to mourn at.

Similarly, the case of Ahmed Timol, a 29-year-old teacher and anti-apartheid activist who was tortured and killed in 1971, reflects the same cycle of state denial and delayed justice. Apartheid police claimed Timol committed suicide by jumping from the 10th floor of the infamous John Vorster Square police station. A 1972 inquest accepted this explanation. However, a 2018 democratic-era inquest revealed Timol had been tortured so severely that he would not have been physically capable of jumping, concluding he was murdered by the police. Former security branch officer Joao Rodrigues was finally charged but died in 2021 before facing trial, after attempting to secure a permanent stay of prosecution citing his failing memory.

South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) has faced mounting criticism for its slow progress in pursuing apartheid-era crimes, often citing challenges such as the passage of time, the death of key witnesses, or lack of resources. Yet, activists, historians, and families of the victims insist that justice must still be pursued. The Cradock Four, like many others, symbolize the thousands who fought for South Africa’s freedom but whose deaths remain unresolved.

As the reopened inquest proceeds, South Africa finds itself at a critical moral and historical juncture: whether to finally deliver justice for past atrocities or allow the wounds of apartheid to fester unhealed. The families of Calata, Goniwe, Mhlauli, and Mkonto and countless others, are still waiting to bury the truth with dignity.

Leave a comment